The coal trunk line

The coal trunk line removes strategic threat

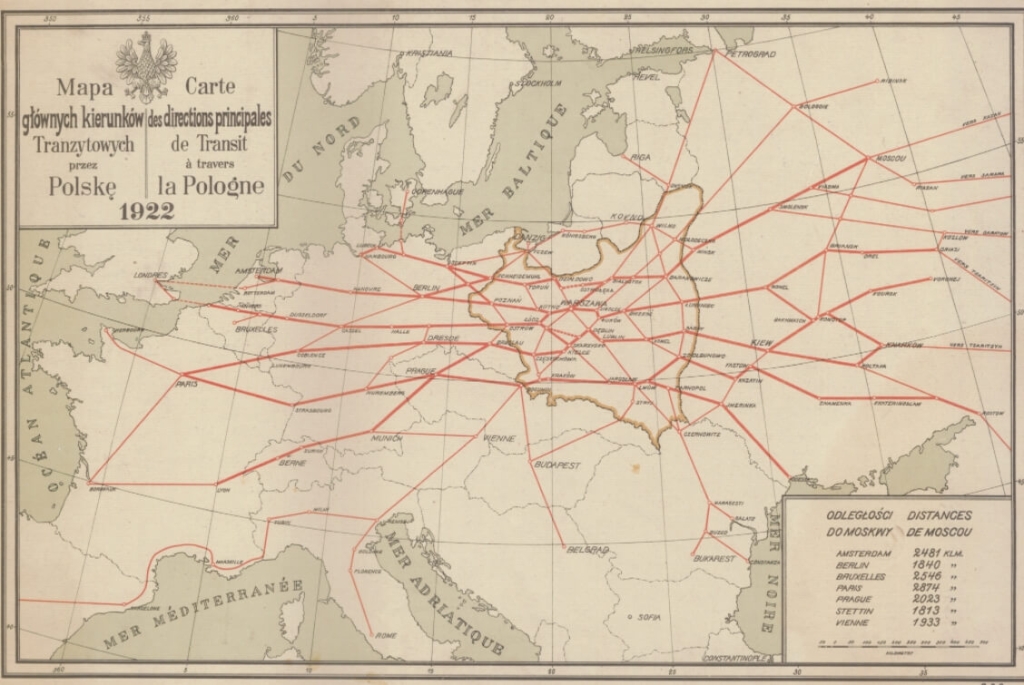

A major logistical challenge for Gdynia, the newly built Polish seaport, was its connection to the rest of the country. The Polish railway network, inherited from the partitioners, had been devastated by warfare. 50 per cent of railway bridges lay in ruins or were unusable. More than 65 per cent of railway stations were destroyed.

Railway lines were inefficient and the resulting national borders crossed them in unexpected places. An example of this was the Kluczbork corridor, where a track entered the territory of a neighbouring country, only to leave it immediately. The German side charged lavish tolls for the use of this section. There was also nothing to count on for road transport, as only 5 per cent of the roads were suitable for transporting.

The existing railway line, connecting a short stretch of the Polish coast with the inland, ran through the Free City of Gdansk, whose authorities had blocked the passage of goods in the past. In 1920, during the war waged by Poland, for example, they stopped ammunition shipments under the guise of neutrality.

Moreover, from 1924, Polish relations with Germany began to deteriorate drastically. The customs war that began at that time resulted in a ban on the export of domestic raw materials through the territory of our western neighbour. This threatened to be disastrous, as Germany was receiving almost 60 percent of Polish coal. This strategic threat was to be addressed by the Magistrala Węglowa, a railway line that would directly connect Gdynia with Silesia and enable the export of Polish raw materials.

The construction of this special line, commonly known as the Węglowka, was the responsibility of a joint-stock company, operating under the name of Francusko-Polskie Towarzystwo Kolejowe S.A. (Compagnie Franco-Polonaise de Chemins de Fer). Bank Gospodarstwa Krajowego became its shareholder. The French shareholders were the Banque des Pays du Nord and the metallurgical and armaments concern Schneider et Creusot, which had been part of the Franco-Polish consortium for the construction of the port at Gdynia since 1924. In addition to its share in the consortium, the company was also a shareholder in several mines and steelworks in Upper Silesia. It was therefore in its interest to open a sea route for coal from Poland and to become independent of Germany.

The importance of the Silesian-Baltic railway line was also recognised by the foreign press. While it was still under construction, on 5 May 1931, the Berliner Tageblatt emphasised its importance as follows:

The construction of the Katowice-Gdynia line is changing the face of Europe from an economic and political point of view.

On the first of March of 1933, the Silesia-Baltic railway line was inaugurated at Kasznica station, connecting the industrial region of Poland with the national port on the Baltic Sea. It was 522 km long and was the shortest section connecting Katowice with Gdynia. What was rare in Poland at the time, the section was technologically uniform.

Source: The National Digital Archives.

Source: The National Digital Archives.

From then on, a direct line carried coal from Poland to the Baltic, and wagons filled with minerals from overseas went from Gdynia to Silesian and Czechoslovakian factories. But that was not all. Gdynia’s facilities reached even further. The main line connected with lines running through Lviv towards Ukraine and as far as the Romanian Constanta.

Coal accounted for 60 percent of all transport on the trunk line. In quiet times, the line transported more than 5 million tonnes of coal a year for domestic use and around 10 million tonnes for export. Sometimes the raw material even reached South America. In the opposite direction (especially from Sweden), more than 2 million tonnes of ore were transported annually for both import and transit purposes. In addition to these main raw materials, the line transported more than one million tonnes of agricultural products and the timber industry and almost as much general domestic traffic. This calculation shows not only the nature of Silesian-Baltic transport, but also the changes that have taken place in the Polish economy.

In addition to changing geostrategic conditions, the trunk road also had a positive impact on internal rail traffic. It increased the density of the network, which enabled better use of rolling stock and organisation of transport. It relieved congestion on railway lines that are still used for passenger transport today. It also provided a development opportunity for countries along the north-south line, as the shortest route to the Baltic Sea for goods from Czechoslovakia, Hungary, Romania and Yugoslavia. Despite this, transit traffic on this line never reached more than 8 per cent of total traffic.

100 years later, BGK is already connecting not only Poland, but the entire region. Thanks to the Tricity Fund, of which BGK is the initiator and co-founder, new north-south infrastructure links are being created from 2019. Investments in 3 areas are particularly important: transport, energy and digitalisation. Its portfolio includes a range of strategic investments, from a container port in Bulgaria’s Burgas, to data centres, to photovoltaic farms, etc.

BGK’s ambitions go even further. The bank is already responding to the challenges facing humanity by, among other things, initiating the search for new and healthy technologies. In 2021, the 3W Concept was created, whose search focuses on three resources: water, without which there would be no life; hydrogen, which is the future of energy; and coal, but the elemental one, which allows lighter and more durable engineering materials to be designed (Read more: The 3W concept).